FIBER Festival

Spring 2024An interview with an expert on rave

For the 2024 edition of Amsterdam’s music & arts festival, FIBER, I joined a group of writers publishing a variety of features related to the festival’s themes and programmes. Specifically, I was privileged to interview McKenzie Wark about her popular 2023 book, Raving.

Read full article here or below.

Dancing While the World Burns: An Interview with McKenzie Wark

In this interview, Callum McLean explores McKenzie Wark's book Raving and, alongside the writer and media scholar, reflects on raving as a cultural practice and a way to navigate a world in crisis.

In a dizzying world of unfolding, overlapping crises, it’s hard to know what to think – so why not turn away from thinking altogether? Raving seems to offer that promise.

And it was to raving that McKenzie Wark turned shortly before and during the pandemic, after a rare break from publishing since she began taking hormones in 2018. This Wark is introduced in her book as “a middle-aged, clockable transsexual raver”: a new context for a writer already fairly well known beyond her research circle (mostly in media, critical and cultural theory). Raving has since brought Wark to an even wider audience, and the experience of raving itself has also brought Wark to new places in her own thinking. But does raving as a practice not rule out thinking altogether? And what are we to think at all about raving?

To answer these questions, I spoke with Wark a few weeks after her reading and Q&A as part of the context programme of FIBER Festival 2024 – about raving’s power beyond politics, how raving continues to thrive, and how it might help us all to survive.

But what is raving, actually? For Wark, raving is an embodied practice, and also a cultural phenomenon expressed between bodies. More specifically, it’s a phenomenon experienced in a particular context: by Wark, within queer raves in and around Brooklyn around and during the pandemic. This raving – and perhaps raving in general – reflects, and partly resists, dynamics in the world beyond it. But it also tells us something about that world.

Wark, however, might put it differently: “It's a book for ravers. It's a love letter to the [raving] world and to analogues of this world and other parts of the world.” As so often in the book itself, in our conversation she resists disentangling these perspectives when considering her aims: “How do you centre the history of Black and queer people in the production of this overlapping constellation of electronic dance music, the space of the night club and then rave as a specific set of practices and the history within that?”

While Raving confidently takes up this challenge, it’s not a book that offers easy answers to this kind of question. “Raving is kind of a sneaky book,” Wark confirms. “It sneaks in a kind of worldview that engages with certain philosophies into a book about a very specific experience.”

Throughout Raving, anecdote and observation of Wark’s raving experiences often work in this way, to elucidate broader social and political dynamics: to show how ravers are situated in, created by, and reacting against (or at least ‘dissociating’ from) the world outside the rave.

This is also often flipped, when raving and techno themselves come to symbolise and challenge our understanding of time, history, and politics. This is most evocative when Wark wields terms within DJ and club culture as metaphors – synaesthetic descriptors for reality, which seems warped as a result: "Cross-fade to now. That memory track beatmatched to this in the rave continuum" (p. 16); "Sometimes when I'm raving, the theory sequencer kicks off on its own. Concepts dance into the sound" (p. 30).

But it’s also by and large a book for these specific ravers, about these specific raves. Wark explains: “I want to be able to have a space of reflection for the [raving] world itself. Not everyone in the rave world wants that, but for me and others, we'll stagger out of the party and be like, ‘What the fuck just happened? We need to talk about that.’”

This drive is perhaps what makes the book so readable. It’s impossible to resist its thick description of dance floors: from the jumble of jostling crowds and sexual encounters to the phantasmagoria of dancing bodies lost in “ravespace”, transcending to “k-time”. As these seemingly heady concepts imply, those vividly lived moments are often carried to conceptual conclusions, embodying Wark’s more scholarly thoughts about the world at large – but they are also there in service of capturing and doing justice to the uniqueness of those raves. In this way, the book can also be read quite straightforwardly as a rave report, a celebration of raving. “There's moments at the rave that are just so astonishing that you have to rise to the challenge of it,” summarises Wark. “There's a whole history to nightlife and techno and whatever, but the flavour of this one in particular is this very rich, specific thing.”

The alien clamor of computation patterns a chronic 140-bpm situation. The dense, hot, wet, beat-stricken air, teaming and teeming with noise, sticks like meniscus, passing perturbations through skin as if skin’s not there. It’s all movement, limbs and heads and tech and light and air bobbing in an analogue wave streaming off the glint of digital particles. Getting free.Raving, p. 18

The appeal of this style and of these detailed rave reports is self-evident and broad. But it could be broader, clarifies Wark: “I don't want this to be a book for tourists”. Throughout, she obfuscates names of raves and ravers, to protect the culture and individuals within it – from social and workplace judgements of raving’s sexual and chemical liberties, but also from scrutiny around stories of “crisis” and addiction. “There's just so much trauma in this little world that sometimes it comes out in behaviour that you wouldn't accept in the straight world. But here it's like, ‘Yeah, honey, we're all like that.’ So it's about having that compassion for that.”

Compassion and respect, for Wark, are more than just questions of writerly ethics. They define good praxis at the rave, and help distinguish her and her role in the rave from its core characters. “It's all about respect and honouring who really needs these spaces”, Wark emphasises. “For me, at the centre of it are the ‘dolls’: it's certain kinds of trans women, often trans women of colour, who when they show up at the party, it's been blessed. That's the place to be: they feel at home here, at least for now. So this is the place, and let's let them have that centre of the dance floor”.

Despite herself being a core part of this culture, Wark repeatedly insists – in the book, and our conversation – that she is not raving’s main protagonist. Among the colourful characters of Wark’s raves, she defines certain subcultural archetypes defined in contrast to the doll: “coworkers”, who are guests in the rave (“I'm also a ‘coworker’, in this context, just meaning someone with a day job”, she clarifies), and “punishers”, usually cis male dancers taking up too much space (“someone who is going to make it hard to get your rave on” [p3]). While Wark’s subjective experience of the rave drives the book and its conceptual directions, these reflections are not presented as its end goal. Introspection is very much not the point of raving, or of the book Raving. Wark explains: “I think it's more just that sensibility of making oneself a minor character in this, or making one's type of person a minor character in the history… this has all been about somebody else from the jump. It’s to honour that.”

In fact, Wark emphasises, losing sight of this is what threatens raving, or kills its buzz. The self-conscious fetishising of authentic rave – and its dolls – is what draws the punishers. “Wherever it looks like there's people actually having a good time, then a style has to be extracted from that to be turned into a commodity to sell,” explains Wark. “But it won't be the good time: it'll just be a sign in place of the good time. That can't work! You have to work it, you know. Like the saying goes: ‘work it!’ [The rave] is not something to consume, it's a thing you make.”

Yet this cycle of commodification is nothing new, and raving – in queer Brooklyn and elsewhere – can survive it. This co-opting or, to use a term from the Situationists (one of the core topics of Wark’s previous research), “recuperation” is a feature that seems fundamental to cultural (re)production in late capitalism. “That's the history of Black culture: it’s been recuperated for 100 years. The whole history of recorded music has been involved in this recuperation: this is just the latest wrinkle on it…

“For now, [queer Brooklyn raving] is ongoing! The rents are fucking killing us. That's what'll drive us out of the city, eventually: landlordism... Otherwise, as long as we can make rent, we'll make a world: we'll make a world and it’ll be fabulous.”

***

In this cat and mouse game, rave is pitted against its enemies: gentrification, landlordism, commodification. So it’s tempting to see raving as an antidote to capitalism itself. Since its inception, rave has exuded this kind of mythology: that on its dancefloors are sown the seeds of change, that its sounds carry emancipatory possibilities. “We did that in the ‘90s; I'm just so over it!”, Wark scoffs. “Rave is not utopia. It's not transcendent. It's not resistance. It's just not! On the other hand, it's not [only] escapism either. It's a situation.”

Does that mean rave is not political? On this matter, Wark is passionate and well prepared, so it’s worth quoting her at length: “People always want a politics that’s actually somebody else's: it's from some other place… it's this middle-class straight person's idea of where Politics is, with a capital ‘P’: the political. But politics is every single move you make on the dance floor. At a good party, everybody's there: every kind of body is there – people with very, very different kinds of neurodivergence are there sharing space, and disability and mental illness… On top of all of the genders. It will be a multiracial space.

“We're figuring this out with every single move… We haven't solved racism or whatever – that’s not what this is – but we’re just figuring out how to cohabit this space without having that meta-level commentary about this all the time. We're just together – and working on producing a non-individuated body, working on non-singular being. A good dance floor does that. It's kind of astonishing when it comes off.

“We're all supposed to have these fucking obligations for other people's politics, and no one feels obligated to us. It’s like, Where are you fuckers for the dolls? For the trans women in this town? You don’t show up for us. So fuck you: we're supposed to show up for your thing now?”

“I’m putting it a bit harshly”, Wark admits, but it’s because we seem to have touched on the crux of the matter. For those who don’t “need” the rave, these questions are academic. For those who do, its meaningfulness is intuitive, visceral – and the stakes are infinitely higher. “People who want to do other kinds of politics, what's their responsibility to making it possible for us to do this thing – and without which some of us wouldn't still be alive? I really believe that the dance floor is keeping some of my friends alive and sometimes myself, frankly. So yeah, who's committed to that?”

To exist inside those beats is like hacking into a new brain, one that doesn't hate my body, that can run on the DJ's track and not the track of my anxiety, that allows my body to be a fucking body.Raving, p. 80

Raving might not be political in a narrow sense, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t significant, or that it doesn’t have something to say about, or to teach, the reality beyond it. Wark articulates: “There are different functions in the world, and I truly believe that there is a power in politics, but there is also a power in culture, there is a power in the social, there is a power in aesthetics.”

And this is where raving’s connections to a wider world materialise. Raving won’t start a revolution, but it does reflect seismic changes on a global scale. “I feel like one of the things that's going on is that [the rave] is a place where people take the emotional outpour of what's really a world historical situation”, Wark clarifies. “That not the world, but a world is ending – and we know it. We all know it. So what's the art form that articulates that? Well, one of them is definitely this.”

The book ends on this note, which seems both apocalyptic and oddly hopeful at the same time. Are we just raving to distract ourselves while the world burns? Perhaps, but in this moment of shared catastrophe, raving presents a practice that turns to the collective nature of our predicament – and that centres those who are usually sidelined from our idea of who gets to matter in this struggle. The rave offers answers here: “Here is a place where an artform is working through that intense emotional experience. And it's going to centre people for whom the world never existed to end in the first place, you know? Trans women of colour never had a fucking world in this country.”

This turn to raving’s main protagonists is in this way a double one. It affirms the particularity of their traumas and also their relevance for us all – not to fetishise them, but to champion them and their modes of survival. In particular, Wark articulates the cultural connection of raving – as a personal, embodied practice – to our world historical moment through the concept of dissociation. “I think [dissociation] is a different sort of aesthetic category based on an experience that gets pathologised but is actually a sort of social artefact.” To be clear, Wark cautions, “dissociation is not a good thing. To be exiled from your own body is really not fun. On the other hand, if it is going to happen, how is it a thing that you can train to give you experiences that enable you to re-associate to something, to re-associate to the collective body of the dance floor, for example. It’s not going to work for everybody, but I think for some trans people and otherwise traumatised people, there's things that we make dissociation do for us. And [the question] is, maybe, What if dissociation was a sort of aesthetic key to the era?”

As Wark explains, the concept of dissociation responds to our era of crises in a similar way than “alienation” once worked, in the ‘60s and ‘70s – to link our individual experience to global processes. Then, the concept argued, we lost our collective power. This time, it’s about coming back together.

There is merit in sharing the pessimism. Everyone is experiencing it. Helps us all feel our way through it. A commiseration. An articulation. It makes it okay not to pretend that some big hope is going to save us. It’s about how a person saves herself, inside of this darkness, at the end of the world, by finding some way to exist within it.Raving, p. 85

“Raving is not just a book about the rave”, Wark insists. Of course, on one level it is about the rave as a rave. But it also shows how raving responds to a collapsing world, and how it might offer hope for those of us collapsing along with it. “It’s a book about aesthetics: the aesthetics of dissociation and historical time”, Wark summarises. “[It asks,] How do we manage being in the world at this time, when a world is ending?”

Faced with questions of this scale, Wark insists, there are no easy answers or magic bullets. But there is always raving.

Rewire Reflections

April 2024Zine published during Rewire 2024

For the 2024 edition of The Hague’s music & arts festival, Rewire, I joined a group of writers publishing a zine on and during the festival. Read my three pieces below, on Julia Holter, Simo Cell and ‘echoes of rave’s ghosts’.

Read full zine here

Echoes of Rave’s Ghosts

It’s witching hour at the Lutherse Kerk, and Maxime Denuc is channelling rave’s ghosts with an organ robot: psychedelic arpeggios, dubwise riffs and trance hooks. A rapt crowd listens mostly sedate in the pews, except for several heads pumping uncontrollably to the shadow of an absent kick drum. A gun-hand pumps the air. Some- one in the crowd calls it “organ techno”, but their ecstatic whoop whoops at its climax fail to egg on the missing DJ. The hype filters through 18th-century pipes to the robot behind – indifferent, unshakable from its machine pulse.

Rave’s ghosts abound in and beyond Rewire.

Rave revival, resurrection, retro-futurism – the obvious signifiers have proliferated, evolved, echoed throughout so much electronic music since the second summer of love. Our endless rave referencing today can go far beyond cynical nostalgia. These persistent ghosts hint at the enduring appeal of the past’s promise of emancipations from looming and present social, political and ecological collapse.

As in every utopia, there’s a flipside to this coin – in rave’s case, a darkness present in hardcore and jungle since the beginning. Something alluded to by a Coco Bryce EP title from a few years back, Worries in the Groove, and extremified by darkcore. Let’s call this euphobia: a pleasurable paranoia that mirrors the cathar- sis of horror movies – so often sampled in dark jungle.

In Paard’s main room, Aïsha Devi seems hellbent on ushering in the four horsemen. She unleashes sub-bass tsunamis and percussive artillery, a war zone of euphoric destruction. Her Valkyrie silhouette flanked by glittering, patchwork banners billowing in a wind that seems to emanate from the speakers. No breaks, sirens or 303s here: this new entry to the apocalyptic rave songbook is a familiar battle cry, a chorus of voices calling between the future and somewhere primordial.

These spookiest of rave’s ghosts, this darkness invigorates the raver’s gesture of abandon. Especially for

the most vulnerable bodies, there’s a dark joy in opening up to the risks inherent in chemical, social and sexual experimentation – a choice to be exposed to risks under your control rather than those outside it. Channelling these ghosts gestures beyond and reinforces the bound- aries of the rave haven for those gathered safe within.

Noise Diva, whose DJ alias has long sheltered her from expectations she faced in the art world, channels a dark rave energy with newfound urgency. Rave offers her the power to champion pro-Palestinian causes, embrace her Syrian heritage – distorted breaks, broken techno and hardcore adrenaline wrap around Arabic pop and hip-hop – or be free from having to speak for it.

Rave’s ghosts haunt us, protect us, and will continue to do so for as long as we need utopias: for as long as the emancipation it always promised is denied to us, and especially to those for whom rave’s safe spaces are most essential.

Julia Holter reviewed Paard I, Friday

In times of chaos, lightness. That’s how Julia Holter’s performance burst into Paard this Rewire: enshrouded, surrounded, unflappable.

“Hear the hocket babble / Save our souls and laughter.” Mid-set, Holter wrenches out Words I Heard: the barest, most openly despairing track from her 2018 album Aviary, whose anxious cacophony responded to the unfolding crises of the previous years. She recalls this in her first words to the packed venue – how that song was bled out of circumstances only more dire today: “Now, it’s controversial to say ‘Ceasefire Now’... I wanted to say ‘Free Palestine’.”

Against despair, determined to hope – so hits Holter’s first show touring her new album Something in the Room She Moves. A new line-up adds punch and immediacy to earlier tracks Sea Calls Me Home and In the Green Wild: to their rhythmic lightness, trip-hop synth smashes from percussionist Beth Goodfellow; to their subtle undertow, fretless basslines seesawing vigorously from Dev Hoff. Even longtime collaborator Tashi Wada cranks up the synths and pipes, once textural, now tectonic.

It all comes together strongest on new tracks like Sun Girl and Something in the Room She Moves. During these, Holter twice abruptly stops the show right before a song’s climax: “Can we do that again?” she echoes into infinity, galactic delay still on the mic. Second time lucky, she hits the right button and an organ stab skyrockets Talking to the Whisper stratospheric.

Because ultimately it’s Holter at the wheel, pedal to the metal and yet careening this show beguilingly close to a cliff edge, past which wonder and horror beckon.

“Take my hand ... / All I have to design / Fog reclining behind / Something on the horizon.”

Holter’s music has always oscillated between light and dark – chamber pop twinkle and cerebral abstraction – but it’s the moments that reconcile these two extremes that hit hardest. Silhouette and closer Betsy on the Roof bring this home: arrangements gripping and yet elusive, gesturing somewhere almost visible, if only you craned your neck a little more. Holter’s voice at its most taut, yearning interdimensional. Almost lost among the dexterously stilted shuffle, Holter is the undying voice in the smoke, trilling crystal clear through the fog.

Creating imaginary worlds is simply the very essence of our humanity’: Simo Cell interviewed

Over the years, Nantes-born Simo Cell has become a reliable source of club bangers: explosive, futuristic floor-shakers with strong roots in Bristol and UK sounds, dub and hardcore. In 2023, his first full-length Cuspide des Sirènes took these and a wider palette of sounds and created an immersive, cinematic journey, borrowing heav- ily from the fantastical video games of his childhood. This was not the first time rave and UK styles had intermingled with video games: see the jungle soundtracks of the 90s, or grime’s heavy borrowing from fourth and fifth-gen console sounds. But Simo Cell took rave-game synergy to new levels, each track corresponding to a level in this expansively realised quest towards a magical lake called Grand-Lieu. There’s even a Gameboy cartridge, where this world is rendered in 8-bit retro glory.

This nexus shouldn’t be surprising: electronic music and video games both have peculiarly generative, animative power. Power to generate movement, and to animate new realities. In his own words, Simo Cell introduces us to his own recipe for bass world-building.

“I am fascinated by the impermanent nature of our being and the ever-changing, ever-recomposing world. This is what I try to capture when I go to the studio and switch on my machines. A meeting, a phrase, a smell.

“The conception of the album lasted three years, and during this period, I had an obsession with butterflies through reading Emmanuelle Coccia’s work Métamor- phoses. The insect that crawls, transforming into a flying being, feeding on light. There’s an almost chimerical aspect to it.

“Hence the Sirens [of Cuspide des Sirènes]. As I was writing, there were many voices reminiscent of the Sirens’ songs, notably because I worked with AI software called Vocaloid. This fantastical aesthetic accompanied me during the composition of the album. And naturally, I began to imagine the possibility of creating a world around the album over time.

“Spending three years on a record leads to introspection, and I drew on my childhood memories to imagine a story inspired by Zelda: the side quests, the psychology of the characters, the psychedelic witches, the Zora fountain.

“Since my childhood, I’ve been told all sorts of legends about the lake that borders the village of my grandpar- ents, where I composed part of the album: a village engulfed by the waters, a mad horse that roamed around the lake searching for walkers to kill... The legend of Grand-Lieu began to take shape in my mind.

“Creating imaginary worlds [whether in video games or music making] is simply the very essence of our human- ity. Everything around us in our human lives was first imagined in a human brain, from the roads to the chairs to our clothes... Literally everything that frames our lives is the product of our imagination. We live in Minecraft, if you think about it for two minutes. Humans are beings of imagination.

“Similarly, when I go to play [music], I see myself as a creator of movement. I think it’s universal, it’s central. It’s just the form that changes a little. Today, it manifests through the sound system: [It’s] about the bass. Infrabass can’t be heard, but it shakes you. It’s these super low waves, something akin to the earth moving. It’s really organic, in a way.

“But for me, the rave – the act of coming together to dance and share a moment of collective frenzy – has also always been there.”

Listen Amsterdam

Autumn 2023Zine for KEF

For their launch of a series of global listening events, Hi-Fi brand KEF (also behind music editorial platform Sound of Life) published a zine on Amsterdam’s (electronic) music scene and nightlife. I wrote a few short pieces on elements of that (including labels Music for Memory and South of North) and interviewed three DJs (Marcelle, Carista, Noise Diva) for what became a feature titled ‘Sound of the Underground’. See highlights below.

Read here

For their launch of a series of global listening events, Hi-Fi brand KEF (also behind music editorial platform Sound of Life) published a zine on Amsterdam’s (electronic) music scene and nightlife. I wrote a few short pieces on elements of that (including labels Music for Memory and South of North) and interviewed three DJs (Marcelle, Carista, Noise Diva) for what became a feature titled ‘Sound of the Underground’. See highlights below.

Read here

Photo: Matilda Hill-Jenkins

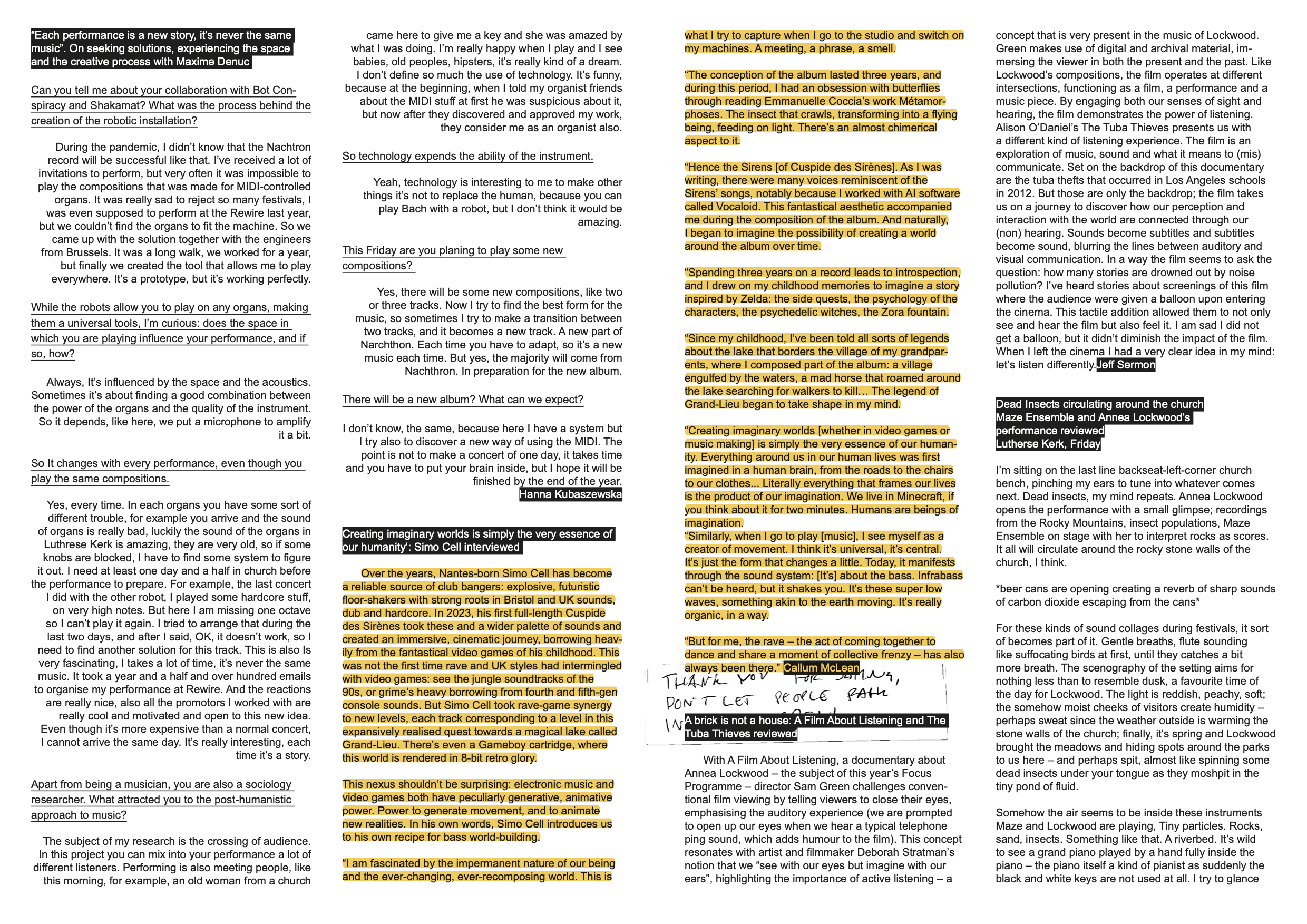

[Intro to ‘Sound of the Underground’ interviews]

Like the city itself, Amsterdam’s club culture is full of contradictions and qualifications. Steeped in counter and queer culture, but per- haps less so than somewhere like Berlin. Deeply international and rooted in Black history, but more quietly than New York or London. Rich with local musical traditions, but often skewing hip, towards UK hardcore, Detroit house or German techno over homegrown gab- ber. Progressive and fluid—but still somehow catching up to other capitals. Ultimately, this means its most vibrant scenes and figures are often found at the fringes.

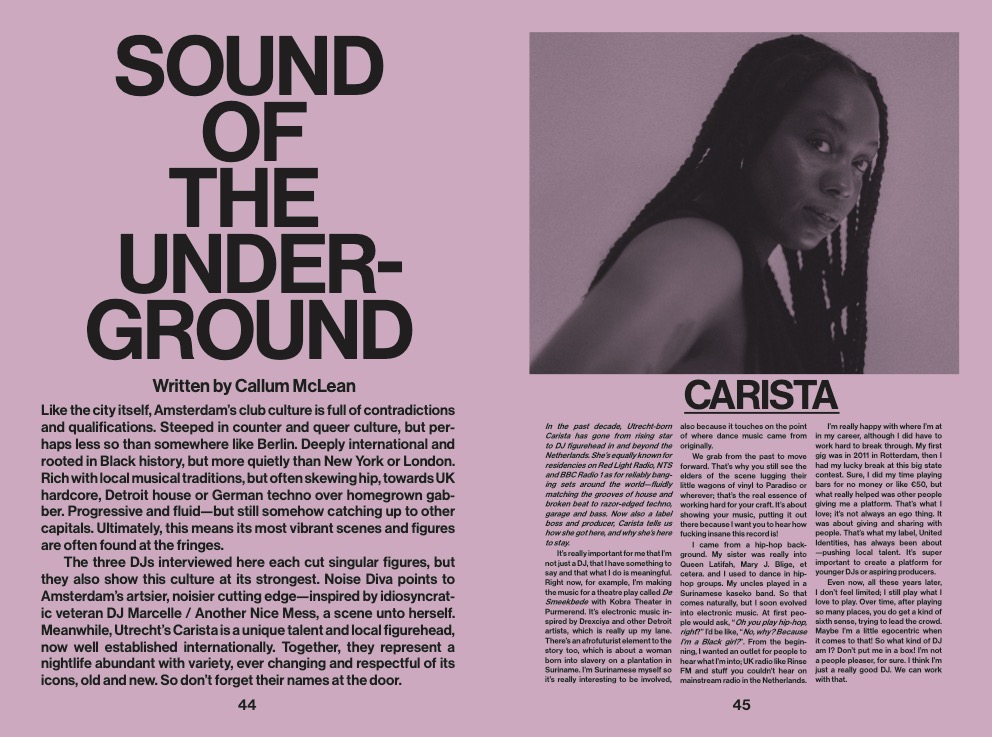

The three DJs interviewed here each cut singular figures, but they also show this culture at its strongest. Noise Diva points to Amsterdam’s artsier, noisier cutting edge—inspired by idiosyncrat- ic veteran DJ Marcelle / Another Nice Mess, a scene unto herself. Meanwhile, Utrecht’s Carista is a unique talent and local figurehead, now well established internationally. Together, they represent a nightlife abundant with variety, ever changing and respectful of its icons, old and new. So don’t forget their names at the door.

[Note: images in .pdfs below inverted, see full .pdf for how they were originally published]

IFFR

Published 2023, 2024Programme texts for 2023 and 2024 editions of International Film Festival Rotterdam.

I contributed five film texts for IFFR 2023 as their communications team set about developing a new style guide for the festival, including more accessible and detailed film descriptions. The resulting texts were published on the online programme and in the printed catalogue distributed with the national Volkskrant newspaper.

I did the same for a further four films in the 2024 edition, including the opening film, Head South.

See all full film texts via the links to the right, or read a selection below.

Alien Food (dir. Giorgio Cugno)

Gagaland (dir. Yuhan Teng)

Não Sou Nada – The Nothingness Club (dir. Edgar Pêra)

New Strains (dir. Artemis Shaw, Prashanth Kamalakanthan)

We Had the Day Bonsoir (dir. Narimane Mari)

Head South (dir. Jonathan Ogilvie)

La Bête (dir. Bertrand Bonello)

Mars Express (dir. Jérémie Périn)

Una Historia de Amor y Guerra (dir. Santiago Mohar Volkow)

Mars Express (dir. Jérémie Périn)

Forget Terminator’s T-1000. In this hard-boiled sci-fi anime, the robots aren't the real villains. Or are they?

It's 2200, and private detective Aline is hired to track down a hacker, together with partner Carlos Rivera: an android ‘backup’ for her friend who died five years ago. Their investigation spans Earth and Mars, firefights and heists. At every turn the case peels back a new layer of intrigue, corruption and the human race's uneasy relationship with their robot co-habitants.

This first feature from Jérémie Périn stands confidently among the heavyweights of science fiction, drawing equally from Philip K. Dick and anime classics. But while treading familiar ground from the canon, Mars Express is still full of surprises, twists and unforgettable quirks. It asks questions familiar to the genre, but with a freshness that suggests new answers. And those grand enquiries and its lightest touches are handled with equal elegance – thanks to rich, tactile worldbuilding that inspires both wonder and humour, charm and horror: from a mid-surgery software update to a shop display of spare, blinking eyeballs. It might take a second to tell 'augmented' humans from 'organic' robots, 'brain farmers' from 'jailbreakers', but who cares when it's this much fun?

We Had the Day Bonsoir (dir. Narimane Mari)

A love song for the dead, We Had the Day Bonsoir reaches beyond mourning and eulogy – towards something eternal. With fragments of intimate documentary sound and film, Narimane Mari captures a vivid yet oblique portrait of her late partner, the painter Michel Haas. It's an ode to a specific life through the eyes and ears of his lover, but also to life itself.

Through her eyes, we see someone full of that life right up to his final days: on all fours painting in the dirt, laughing childlike at Chaplin, swearing at the camera. But Mari seems more concerned with listening: to voicemail epiphanies between the two lovers, to an unanswered plea from Haas's doctor, to the lapping of waves. With these lyrical fragments, the film often ponders along with Haas and Mari about the impossibility of endings. How the ‘illusion’ of time passing clashes with the will of human stories, and of art, to endure.

“Every soul is a melody that needs to be renewed”, Mari says, bidding us listen. Because, the film keeps reminding us, what we see intimately of Haas and his work is only a glimpse of what always remains – just off frame, out of earshot, after the final cut.

New Strains (dir. Artemis Shaw, Prashanth Kamalakanthan)

This cheerfully humdrum rom-com presents a very homemade slice of first-lockdown life. But can its squabbling couple make it through a mysterious pandemic? Co-writers and filmmakers Artemis Shaw and Prashanth Kamalakanthan play Kallia and Ram: young lovers vacationing to New York just as the pandemic unfolds. They’ve already descended into petty name-calling when the travel ban prolongs their trip indefinitely, trapping them in Kallia’s uncle’s apartment.

New Strains is as much a relatable account of the first lockdown as it is a sketch of its particular effects on this peculiar couple. Semi-improvised and shot on a Hi8 camcorder that Shaw and Kamalakanthan found during their own real lockdown, its grainy VHS footage nails the frustrations of personal and creative helplessness in quarantine. A production defined by the same constraints it depicts, it similarly makes the best of a bad situation.

All of which makes it a uniquely authentic pandemic film – full of neat, oddly poignant touches that capture the highs and lows of lockdown relationships. Failing to connect meaningfully over FaceTime gym sessions, dreams of finding lost trousers in the park, bathwater spilling under the shower curtain as the second person gets in. All these sharply observed moments construct a portrait of two lives lived too close, in a shrinking domestic world: lives trying and failing to become one.

Não Sou Nada – The Nothingness Club (dir. Edgar Pêra)

A surreal psychological thriller to get lost in, Não Sou Nada (“I Am Nothing”) draws viewers into the demonically kaleidoscopic world of Portuguese modernist poet Fernando Pessoa. It is the most ambitious film to date from Edgar Pêra, whose broad and striking filmography was celebrated in a career-spanning retrospective at IFFR 2019.

Pessoa famously published under many heteronyms: around 75 different names, each with fully fleshed-out backgrounds, styles, appearances and philosophies. Taking this a step further, Não Sou Nada gives flesh to these characters, all working together under Pessoa, enacted by Miguel Borges, at the publishing house The Nothingness Club.

Though mostly similar in appearance, the heteronyms differ hugely in personality – above all, the gleefully unhinged Álvaro de Campos, enacted by Albano Jerónimo. These clashes start to become indistinguishable from dramatic rifts in Pessoa’s psyche: as he is increasingly beset by philosophical turmoil, his heteronyms are murdered, one by one. Meanwhile, Victoria Guerra plays a double role as Pessoa’s Madonna-mistress Ophélia: at once a saintly psychiatric nurse and duplicitous femme fatale.

In this way unmistakably noir, the film nevertheless presents no murder mystery nor nihilistic twists. Instead, its shadow play of sensations and emotions finds the perfect analogue for Pessoa’s poetry: bewildering and beguiling, as it vividly explores paradoxes of the heart and mind.

John Beltran

Interview for DekmantelMarch 2022

Feature for Dekmantel 2022

I talked to the wonderful John Beltran ahead of a one-off live performance of his classic album Days of Blue, during the 2022 edition of Dekmantel Festival in Amsterdam.

Read here

I talked to the wonderful John Beltran ahead of a one-off live performance of his classic album Days of Blue, during the 2022 edition of Dekmantel Festival in Amsterdam.

Read here

Finally, Dekmantel's long-awaited 2022 edition approaches. And on Thursday night, the Muziekgebouw aan 't Ij will play host to one particularly special set, originally billed for 2020: an exclusive live performance of John Beltran's classic 1996 album Ten Days of Blue.

Now 26 years since its release, Callum McLean caught up with Beltran to return to the origins of the record, and to catch a sneak preview of what to expect from this one-off show. They talked about how Ten Days of Blue went from being an unambitious, lo-fi record to becoming an ambient techno classic – and how Beltran is revisiting the album for this once-in-a-lifetime performance.

For an album that has inspired multiple generations of electronic music fans, Ten Days of Blue has fairly humble origins – and some unexpected stylistic influences. So tells its creator John Beltran, dialling in from his hometown of Lansing, Michigan. "At the time I was in the middle of this new age, ambient phase," he tells me. "Like, I was really into CDs of just whale sounds! Seriously, that was a thing in the early '90s."

Maybe this comes as less of a surprise to some readers now than it would have ten years ago. A lot of the ambient and new age music that inspired Ten Days of Blue – as well as the chillout and ambient techno records that also drew from those genres – have only achieved respectability pretty recently. After a decade that revived and reissued everything from Mort Garson's Plantasia to '80s spa tapes and Japanese environmental music, these genres have reclaimed a new kind of cultural cachet that would have seemed laughable before. New age became all the rage. Yet, Ten Days of Blue has maintained a particular kind of currency with certain electronic music fans that both predates and goes beyond this revival.

The album has been highly regarded and sought after pretty well since its release, with high demand for early Beltran records leading to a controversial reissue of Ten Days of Blue by Peacefrog in 2018. Even Paul McCartney was supposedly once seen with a copy. To illustrate this lasting resonance, Beltran tells an anecdote from a recent set in Colombia. Opening for Beltran's set, a younger Colombian DJ gestured enthusiastically at him, saying only "Ten Days of Blue!" and tracing a tear down his cheek. "That's all he said! I think that's a good thing? Emotionally, the record stands the test of time. I think it translates to anyone who's serious about underground or electronic music, and crosses generations."

But this was as much of a surprise to Beltran as anyone. "This record was never meant to be anything special", he insists. "I put a lot of stock into my record on R&S from the year before, Earth & Nightfall, but then [London record label] Peacefrog came calling. I meant Ten Days of Summer to be more minimal, if solid – I definitely wasn't expecting it to get much attention! It was always going to be as efficient of a record as I could make."

What's more, it's a record that technically should never have been released. At the time, Beltran had an exclusive contract with R&S. "Renaat [Vandepapeliere, co-founder of R&S] called me up one day and said, 'Why is there a blue record of yours on my desk right now?' I was like, 'Uh, is there?'", remembers Beltran. "I hadn't even read the contract when I got it from R&S! I was just happy to sign."

Perhaps another reason for the record's enduring appeal is its warmth. Tracks like 'Flex' and 'Venim and Wonder' are built around techno hi-hats and IDM-style drum programming, but the rest feature almost no drums at all. Instead, the predominant sounds are a highly melodic staccato of featherlight synth sounds and aqueous, billowing pads. "All these sounds I was using were pretty organic, world music textures (I was into Peter Gabriel at the time), but I put them into more techno, rhythmic forms."

In this way Beltran seems to have departed from the Detroit techno scene that he'd embraced early on, having grown up in nearby Lansing. What was it then, I ask, that drew him later to making much more introspective, softer music? "Growing up!", he chuckles. "I didn't want to just be in a club all the time. I listened to so much other music, so I was just moving past these more mechanical sounds."

"But you'd be surprised what electronic music producers listen to", Beltran points out. "I asked Derrick May what he was listening to back in the '90s and he said TLC! For me, it was a lot of Sting – Ten Summoner's Tales. That lushness was really inspiring for me at the time, and that's where my headspace was. I wanted a more elegant approach to electronic music. I wasn't so much into the dirty side of things."

In casting his musical net so wide and unpretentiously, Beltran finds himself in another way aligned with a newer generation of electronic music listeners and producers. For example, Beltran has collaborated with the famously eclectic Four Tet, as well as Malibu and Baby Blue, both of whom he praises for their trance and pop-inflected takes on ambient and techno. And his own colossal discography has spanned everything from drum 'n' bass to acid jazz and Latin.

So why revisit Ten Days of Blue now, two and a half decades and countless releases later? Beltran certainly started with mixed feelings: "In some ways, I've always been trying to run away from this record. I hate to say that to everyone who loves the record, but when people tell you it's so great, you can't help but think, 'Well shit man, I'm still making music!' I think what I do is pretty good still – I'm ten times the musician I was then. So there's that part, but I'm also really excited. I'm starting to fall in love with the record again!"

Most importantly, the performance gives Beltran the rare opportunity to apply a long career's experience to tweaking a classic release. "I would never changethe record – I love it as it is", he clarifies. "But it's fun to put a twist on things for a live performance. On the one hand, it's going to be almost like a listening party: we're all connected by this record. But I also want to make sure this thing sounds killer, you know? I'll be playing a lot of parts live, but I'm also basically re-producing the whole album right now from scratch. I'm bringing the energy, but the emotion and the melodies will be there in full and up front. I'm really excited about the work I'm doing on the record and what reaction it'll get!

"You want to know another reason I'm doing this? Dekmantel is a pretty fucking huge deal! And I never got a chance to play this record live when I was just a kid, so here you are: I love the record, here it is, and I'm finally here to make it rock."